Spinning toward stronger bones: Artificial gravity shows promise for bones in space and on Earth

Imagine lying in bed for two months — not out of necessity, but in the name of science. No standing, no walking, even showering while staying reclined. Now imagine doing that while being spun in a giant machine, for 30 minutes every day.

To see the effects of gravity on bone health, researchers at The Ottawa Hospital and the University of Ottawa led an experiment as part of an international study to test if artificial gravity can prevent weakening bones and fat accumulation in bone marrow, two major health risks associated with prolonged inactivity and spaceflight.

The study, which took place at the German Aerospace Center, involved 24 healthy volunteers who spent 60 days on strict bed rest, tilted at a six-degree head-down angle to mimic the effects of microgravity on the body. To counteract these effects, researchers tested if a centrifuge (a spinning device that creates gravitational force) could simulate the normal forces experienced during upright posture and movement. Volunteers stayed horizontal for the entire experiment and were randomly assigned to one of three groups: no centrifuge (control), continuous artificial gravity (30 minutes/day), or intermittent artificial gravity (six 5-minute sessions/day).

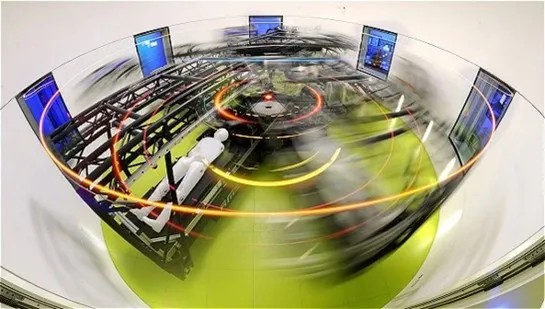

An envihab centrifuge used in the experiment (photo from the European Space Agency)

Results published in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research show that participants who received artificial gravity had less bone marrow fat accumulation and better preservation of bone mineral density, especially in the intermittent group. These findings suggest that artificial gravity could be a powerful tool to protect bone health in astronauts, as well as in patients on prolonged bedrest or with limited mobility.

“This is the first study to show that artificial gravity can prevent bone marrow fat buildup in humans,” said Dr. Guy Trudel.

“This is the first study to show that artificial gravity can prevent bone marrow fat buildup in humans,” said Dr. Guy Trudel, study lead, rehabilitation physician, senior scientist at The Ottawa Hospital and professor at the University of Ottawa. “It opens the door to new technologies that could help patients here on Earth and astronauts in space.”

The study was funded by the Canadian Space Agency, European Space Agency, NASA, and the German Aerospace Center, and builds on Dr. Trudel’s long-standing research into bone and marrow health in spaceflight and rehabilitation.

Authors:

K Culliton, G Melkus, A Sheikh, T Liu, A Berthiaume, G Armbrecht, G Trudel

Funding:

The Canadian Space Agency, German Aerospace Center, European Space Agency, and National Aeronautics Space Administration

Learn more about:

The Ottawa Hospital is a leading academic health, research and learning hospital proudly affiliated with the University of Ottawa and supported by The Ottawa Hospital Foundation.